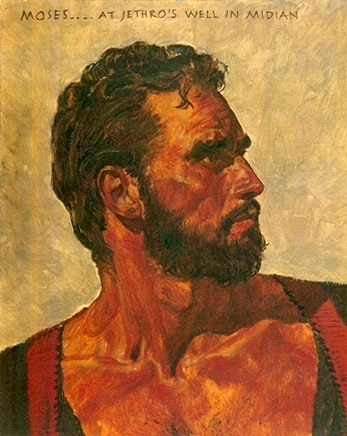

Moses at Jethro’s Well in Midian

When Arnold Friberg was summoned to Hollywood to consult on costume design for Cecil B. DeMille in the remake of The Ten Commandments, he went for a month, interrupting his project of painting illustrations for The Book of Mormon.

Adele Cannon Howells, the President of the Primary Association of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had commissioned Friberg to paint the illustrations. She wanted dramatic depictions she could use to teach children, and she would pay for them herself. On her deathbed she made Friberg promise that he would carry out the commission.

After his month of consultations, Friberg went back to Salt Lake to resume his normal pursuits. The fabled director had taken a shine to Arnold, and a different pursuit ensued. DeMille wanted Arnold back. Arnold did not want to return to Hollywood. He looked for all kinds of excuses to reject DeMille. Mainly, he felt his obligation to finish the Book of Mormon commission.

To bolster his resolve, Arnold took his dilemma to David O. McKay, the president of the Church. He was confident that President McKay would back him up and insist on the obligation to finish the Book of Mormon commission.

President McKay surprised Friberg. The chance DeMille was offering was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. President McKay advised Friberg to take it. The Book of Mormon illustrations could wait, be completed afterwards.

Friberg went back to Hollywood — and stayed for the best part of four years. He and DeMille developed a very close father-son relationship, as Arnold’s duties rapidly expanded beyond costume design.

DeMille would ask Arnold, “How do you see this scene?” Friberg would then paint a very large canvas, rich in imaginative detail. These paintings would become the visual templates in set design and dramatic presentation.

(In a scene towards the end of the motion picture, Moses confers his authority to Joshua. DeMille was going to have Moses do the investiture by raising his arms towards heaven. Friberg told DeMille that was not how it would be done. So in the painting and in the movie, Moses lays his hands on Joshua’s head.)

Charlton Heston was cast as Moses. The prophet’s life was long, and Heston had to age accordingly. As I wrote in my column “The Eight Faces of Moses”, Friberg painted eight portraits of Heston/Moses through these periods.

Scenes may take days or weeks to film, and characters must look the same every day. To guide makeup genius Wally Westmore and his crew, Friberg painted these detailed pictures on artist’s board. No quick sketches, but fully articulated oils. If you look very closely, you can see tiny holes in the corners where the portraits were pinned to the wall of a makeup trailer.

Arnold inscribed above each portrait a few words identifying the scene. But he did not sign his name.

The paintings were given to Westmore. He gave them to his son. Eventually they passed on to his grandson. Having no documentation, the grandson assumed they had been painted by his grandfather.

Early this year the grandson sent six of them to RR Auction for sale in Boston as part of an auction of Hollywood memorabilia — as paintings by Wally Westmore.

As usual practice, the catalog was put online.

This brought an immediate outcry from the grandson of Charlie Gemora, another makeup artist who had worked on The Ten Commandments. Gemora was also an artist and had painted portraits, including a beautiful Barbara Stanwyck in 1942. He claimed that the Moses/Hestons were painted by his grandfather and the auction house was negligent in ascribing them to Westmore.

An energetic dispute between RR Auction and the Gemora grandson developed. Someone suggested to the auctioneers that the paintings might be by Friberg. RR Googled Friberg. That led to me. I don’t know how the Gemora descendant identified me, but the dispute spilled over on to me, and soon I was getting phone calls and emails from both sides.

RR sent me some rough photos by email. I was unwilling to authenticate or give any idea of value until they sent me professional photographs of each painting. If they were by Friberg they would be worth a whole lot more than if they were by either Westmore or Gemora.

Auction day arrived. Should the paintings be allowed to go to auction? RR telephoned and was told I was taking a nap and didn’t want to be disturbed. When I called back, the hammer was only two or three hours away. After talking to me, RR decided to withdraw the six paintings.

Professional photos soon arrived by Fed-Ex. Just a look at the calligraphy across the top was enough to convince me that these portraits were the work of Arnold Friberg. The Gemora grandson had sent a few samples of Gemora’s printing supporting his contention, but this was not a good move.

Even though the paintings were not signed, Friberg was written all over them. Then a friend sent me a copy of a different painting: it depicted two of the same Moses/Heston heads, was dedicated on the front to DeMille, and was signed in cursive on the front by Friberg.

I sent the second grandson an email: “You are barking up the wrong tree trying to ascribe any of the Moses portraits to Charlie Gemora.”

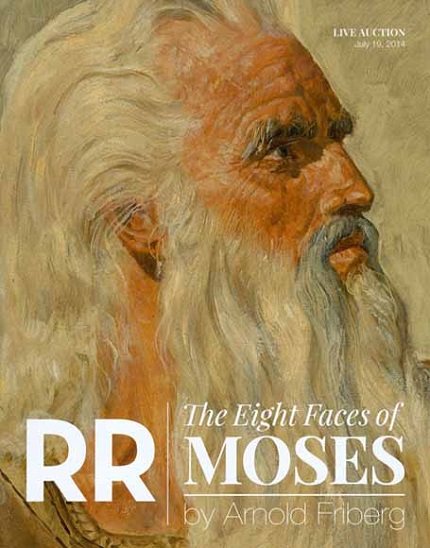

RR Auction wanted to put the paintings in another auction. They then learned that there were eight paintings, not six. The grandson wanted to keep two for himself. I insisted that if the paintings were to be auctioned, all eight had to be included and the sale should not be by individual painting but sold only as a group.

RR then produced one of the most beautiful auction catalogs I have ever seen. They adapted a text I wrote.

All of this took time. They scheduled the sale for Saturday, July 19, in Boston. Working on the last days, I wanted people in Utah to have the chance to see these portraits before they disappeared into some private holding. I thought the ideal place would be in the room in the Conference Center where Friberg’s Book of Mormon paintings have permanent residence.

An emeritus Seventy made all the overtures, but the Church bureaucracy could not work that fast. The argument was advanced that there wasn’t enough time to muster any television and newspaper coverage.

There is a Social Room in the Zion Summit Condominiums where I live. It was not being used on the Tuesday and Wednesday before the sale. We scheduled viewings from noon until 8 p.m. on both days. Frances and I recruited a team of door watchers on one-hour shifts to open the secure condo doors to outside visitors.

Bobby Livingston, Executive Vice President for RR, and Tracey Dexter flew the paintings from Boston to Salt Lake on Monday. Tuesday morning we set up the show. The RR staff had gone to work, and Bobby got important TV interviews on several local stations. Both The Deseret News and the Tribune gave us excellent coverage, with color photos. (So much for the skeptics who said it couldn’t be done.)

My grandson John Hyde was hired to help set up, be security, and do whatever else was needed. He soon became such an effective, personable docent that Bobby wanted to hire him and take him back to Boston.

While Bobby went to Los Angeles on business, Tracey took the paintings back to Boston on Friday. The Saturday auction was postponed until Wednesday, but on Wednesday the auction did not meet the owner’s reserve, and the paintings were passed.

So the eight beautiful paintings by Arnold Friberg of Charlton Heston as Moses remain on the market for either a negotiated sale or a later auction.

Lost for 60 years, the paintings were now known and waiting for a good home. The many who saw it and worked to generate interest feel that the collection, if possible, should stay in Utah, where Friberg's genius is most appreciated.

After note: The DeMille-Friberg relationship led to a warm friendship between DeMille and President David O. McKay. After DeMille's death, his archives were given to the Thomas L. Perry Special Collections division of the library at Brigham Young University.

I don't know how many semis it took to transport everything from Hollywood to Provo, but it was a substantial number. The donation included 1,263 boxes, 38 over-size boxes, 8,000 pieces of production-related artwork, 10,000 stills, and 275 volumes of scrapbooks from 1919-1962.