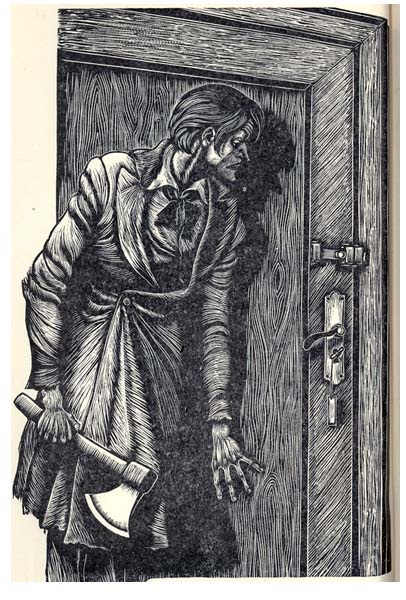

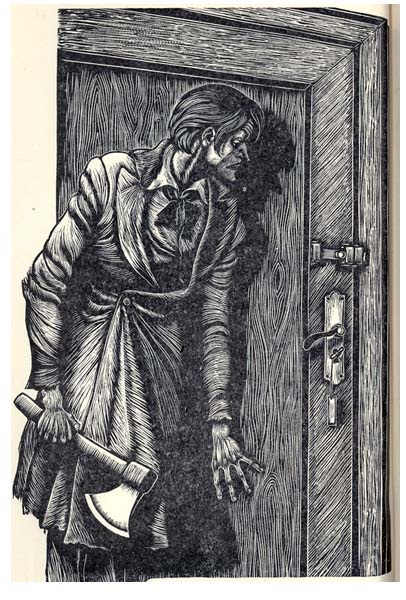

Fritz Eichenberg, Frontispiece from Crime and Punishment.

Writing about Arthur Szyk last week touched off a memory romp.

How did I get into this art business? People keep asking me. I never give them the straight stuff. I always start my story in the middle.

I remember that sometime in the course of eight years in grammar school in Carson City, Nevada, there was in several rooms a miserable reproduction of Millet’s The Gleanors. For years this poisoned me against Millet.

When I was thirteen I went with family to the San Francisco Treasure Island World’s Fair. We visited the major art shows at the fair, my first encounter with really fine art. I probably saw the paintings by William Henry Clapp, but I don’t remember them or any other art.

Ironically, I later sold Clapp’s most important painting in the fair’s pavilion of California art, and I am now writing a major book about him. What I do remember is waiting alone for three hours in a line to see an incredible collection of jade from China.

There wasn’t much of anything in the visual arts in Nevada’s capital. Just as I entered high school, an art and music teacher, Pop Johnson, was finally hired as the school’s seventh teacher. A new school board made this addition in response to years of my father’s crusading.

I had no idea Maynard Dixon had painted the hills behind Carson City. Anyhow, I had never heard of him.

Just as I dropped out of high school, at 17, to enlist in the Army Specialized Training Program, I joined the Three Readers Book Club run by Clifton Fadiman, Sinclair Lewis, and Carl Van Doren, publishing’s three most important literary lions. Fadiman was a friend of George Macy, who had founded The Limited Editions Club and its offshoot, The Heritage Club.

My first purchases were an anthology of the founders’ favorite authors and a copy of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, a reprint from The Heritage Club. A notice at the front explained, “This series of books has been made necessary by the government’s wartime regulations that, whenever a book is reprinted, less paper must be used in the reprint.”

Crime and Punishment was powerfully illustrated by Fritz Eichenberg, probably the best woodcut engraver of the time. (Years later my wife was the visiting teacher to a convert whose mother, a Beverley Hills art dealer, had sold her gallery to Raymond Burr. Paula had inherited a marvelous collection of Eichenberg prints.)

Eichenberg (1901-1990) became famous for his wood engravings. He was born to a Jewish family in Cologne. The destructions of World War I stirred him to anti-war sentiments and contributed to his artistic interest in religion, social justice, and non-violence.

Three Readers did not survive. Wartime restrictions on paper and other factors were against it. They recommended that I shift my membership to The Heritage Club. Either as offerings from Three Readers or an incentive to join Heritage, I soon had three beautiful reissue books: a biography of Rembrandt; Lust for Life, Irving Stone’s biography of Vincent van Gogh; and W. Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, a novel inspired by Paul Gauguin.

The first two were illustrated profusely by reproductions of the artists’ paintings. The third had a different cunning. The first part of the story was illustrated with black and white ink drawings. When the hero makes the decision to go to Tahiti, the illustration is again a black and white drawing that depicts the artist at his easel. But the painting on the easel is a Gauguin landscape reproduced in color, and the rest of the book is illustrated by color reproductions of the real artist’s Tahitian paintings.

These were my introduction to illustrated books.

Needing no further persuasion, I joined The Heritage Club. Membership was by annual subscription requiring the purchase of 12 new books, not unboxed reissues, out of a selection of 15, which included some previous selections, one each month.

Each book was illustrated, printed on good paper, and slip cased. With each book came the Sandglass, a charming and informative bulletin written by Macy that critiqued the book itself, extolled the translator if there was one, recapped the process used to select the appropriate illustrator, and dwelt on the choice of typefaces, my introduction to typography.

I have an original invoice for Victor Hugo’s The Toilers of the Sea. Cost of the book: $3.95, plus 35 cents handling and shipping. If memory serves, when I started, the books cost $3.45. The price was the same for each book in a yearly series.

I kept up my annual subscriptions for more than 30 years, through my service in the military and in college. I took a three-year hiatus while on my LDS mission to France, Belgium, and Switzerland, 1948-1951, but otherwise I was faithful, until I decided Heritage was starting to repeat too many earlier offerings.

Each edition was meant to be a book of beauty and physical longevity. Slowly I was introduced to some of the world’s greatest illustrators.

My first book sent to me directly by Heritage was Tolstoy’s War and Peace, printed in two volumes (in one slipcase) totaling 1672 pages. I was in the ASTP at the University of Utah, and I confess I spent time reading it when I should have been studying calculus. The dean who acted as liaison between the university and the army was not pleased with me.

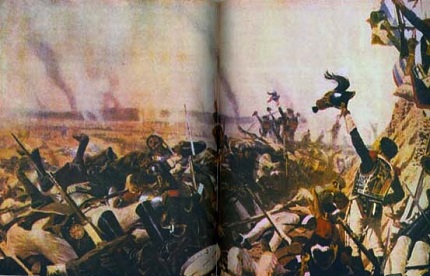

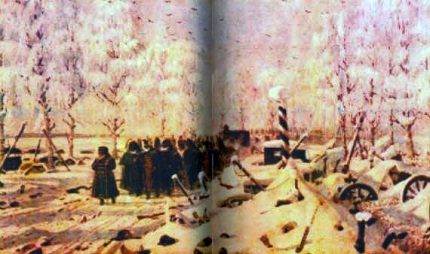

For Heritage, the original highly regarded translators, Louise and Aylmer Maude, revised their translation. More importantly, the two volumes were profusely illustrated by Eichenberg wood engravings and color reproductions of paintings by Vassily Verestchagin (1842-1904). Ah-hah, my introduction to a new painter!

Verestchagin became famous as a battle painter. He was the first Russian painter to gain international renown. In Moscow in 1893, he began creating a series of paintings illustrating Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. He was inspired by Tolstoy’s book.

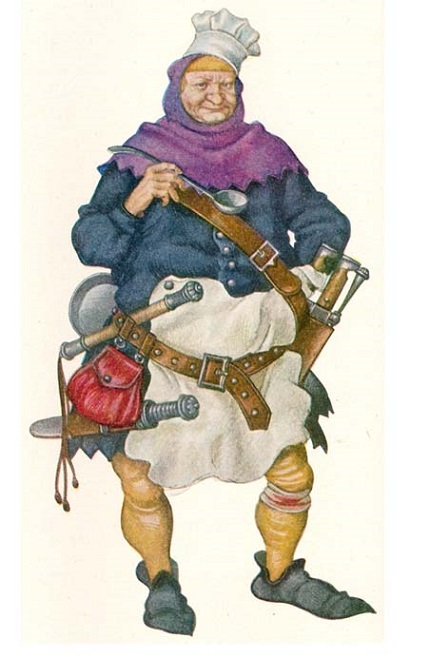

For Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Heritage turned again to Arthur Szyk, who appeared in my column last week. Many of the tale tellers are memorialized by full-page illustrations. It was difficult to choose one for this column. I have selected “The Cook,” which should resonate with readers who eat.

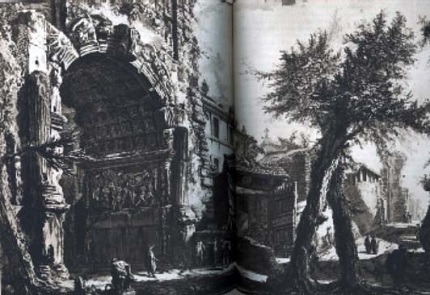

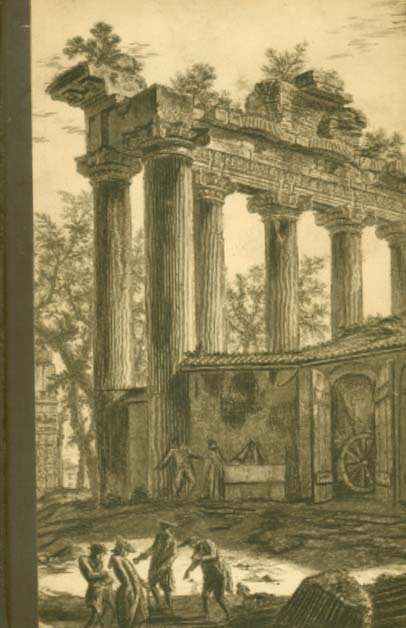

Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire came as three separate books of about 900 pages, each illustrated by Battista Piranesi (1720-1778). Well, no, obviously Heritage didn’t negotiate with Piranesi himself.

Though born near Venice, Piranesi settled in Rome, where for more than 25 years he worked on an extensive suite of engravings, Roman Antiquities of the Time of the First Republic and the First Emperors. These views of what was left of the early greatness of the Eternal City cemented him as an Eternal Master in the art world.

These Piranesi etchings are used throughout the Gibbon’s volumes, often as two-page spreads, and on the handsome cover boards themselves.

Piranesi engraved other subjects, and in 1835-37 a Paris publisher issued 29 folio volumes containing about 2000 prints.

Beowulf, my favorite narrative poem, was illustrated by Lynd Ward (1905-1985), who illustrated several Heritage books. He decided to become an artist when a first grade teacher pointed out that Ward spelled backwards was Draw. His work in woodcuts made him famous. Between 1929 and 1937 he published six wordless novels, their stories being told entirely by woodcuts.

Of the many Heritage illustrators, Ward was the only one I met personally. When I was looking for artists to be represented in a series of traveling shows, he dropped by my house in Bethesda. We spent a pleasant hour, and he gave me an autographed copy of a book of his various illustrations.

James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy was illustrated by Henry C. Pitz (1895-1976), who illustrated more than 190 books, some of which he wrote.

The roster of Heritage illustrators I encountered goes on and on. I suspect that Heritage introduced me to 75 to 100 different artists. I can’t make an exact count because I have given away nearly 80 or so volumes to children and grandchildren.

Through Heritage, a boy from a small town was introduced to a variety of fine illustrative art and was set up for the big stuff when he hit Paris.

That’s the first half of my story of how I became engaged in art, the part that I have never told before.

The rest of the story? Well, maybe in some future “Moments in Art.”